Revising a Course: How to Collect, Analyze, and Apply Student Feedback (Instructional Design Guide)

With the final push of the publish button, your online course is live! A sense of accomplishment and relief take over and you can take a deep breath for the first time in weeks. Any Instructional Designer (ID) will say how the days, hours, and minutes leading up to launching a course is stressful. Teachers and other educators who have had to adapt to remote learning also know this feeling now! However, just because the course is live doesn’t mean that the job is done. What if certain materials don’t resonate with students? What if the directions aren’t as easy to follow as you thought? This is where the course improvement process begins. Collecting, analyzing, and applying student feedback can and will enhance the learning experience. So, how do you navigate this process and where do you start? This blog post has you covered. I’ll explain each step in this improvement process for what I have done for my online courses and programs. Before we begin though, you need to have the right mindset to do this…

Students Know Best

Online education is an ever-evolving process. Just because a technique worked years ago doesn’t mean that it will always be effective. You need to understand that students know best. They are the ones who have experienced your course and their words can give you the necessary guidance to make improvements. Be open minded with the idea of changing the content to better serve your audience. It’s easy to be defensive of your work though, and that’s why I’m asking you to let down your guard a little. If you truly believe that you are right, you’ll have to do more research to understand why the content isn’t connecting with your students. It could possibly be a small revision that will make the stars align. Either way, keep an open mind as your students are not making these remarks to be hurtful, but are providing suggestions to make the course even better.

Just a heads up, this post does discuss surveys, interviews, and incorporating student feedback. It would be wise to double check that these processes do not need IRB approval. Every institution is different so be cognizant of these policies.

With that said, let’s get started!

Creating a Pilot Program

Depending upon where you are in your course’s timeline, this may or may be feasible. If you have enough time though, I would always recommend conducting a pilot program. Why? Pilot programs provide critical information ahead of time before the launch of the course and will provide clarity on areas of opportunity. Most instructional designers will review their own courses before the launch date and will ask their colleagues to do the same. This is a great practice for catching quick fixes, however, these colleagues are not your intended audience. Just because they understand your instructions doesn’t mean that your students will.

To give you an example, my team conducted a pilot program on a series of online technical leadership courses. The IDs on the team went through the pilot program and identified areas for improvement. When the students went through the program though, they identified different areas and actually loved some of the content that the other designers wanted to revise. This happened because the students had different perspectives compared to the IDs. Paying closer attention towards their wants allowed us better speak their language and focus on what truly mattered. If you are able to conduct a pilot, you’ll need enough time to implement the changes so expect anywhere for a 3-6-month turnaround as these revisions will be on top of your other typical responsibilities.

Using a Mixed Methods Approach

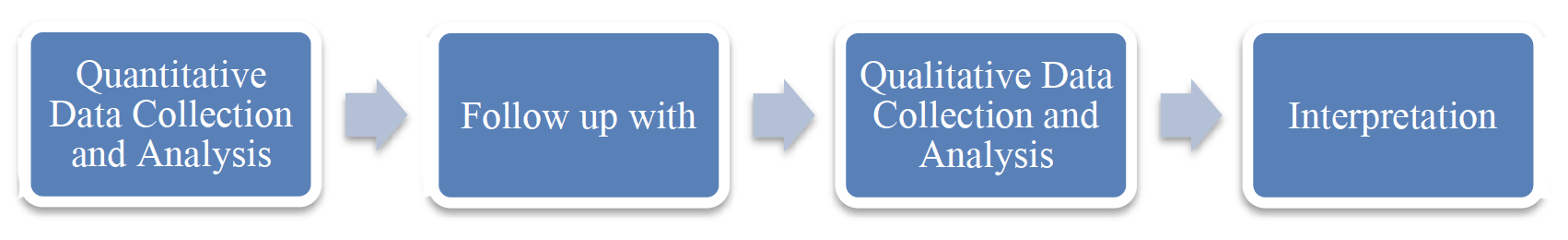

There are multiple ways to approach collecting and analyzing data. It all comes down to what the project calls for in regards to time, energy, and resources. If your project only needs some fine tuning, then a small sample size for a qualitative or quantitative approach could get the job done. My personal favorite is to do an explanatory sequential mixed methods approach. These complicated words translate to a design in which the researcher begins by conducting a quantitative phase first and follows up on specific results with a qualitative phase. The qualitative phase is implemented for the purposes of explaining the initial results in more depth, and it is due to this focus on explaining results that is reflected in the design name (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011, p. 82). You can see the framework below:

Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Approach by Creswell and Clark

Basically, start with a survey (quan approach) and then use the survey findings to influence how you’ll structure the interview questions (qual approach). The answers to these interview questions will provide an overall explanation you can use for revising the course’s content. This design certainly has its challenges and advantages. As you can probably guess, the challenge here is that this process takes time. To me, it’s worth it because the advantage of this style over others is the level of high-quality feedback you can use for improving your course. A mixed methods approach will also provide you more opportunities to ask questions and dig deeper than just surface level answers. For example, let’s say you anticipated your students answering the survey questions in one manner and instead, they answered the complete opposite way. You will obviously want to know more about these responses instead of making an educated guess as to what happened. This mixed approach creates an opportunity for you to dig deeper and find out more information behind the unexpected survey findings.

Designing the Survey (Quan)

For designing the survey structure, keep it simple by using 1-5 Likert scale and multiple-choice questions. You can use different scales for assessment such as highly engaging to not engaging, highly valuable to not valuable, strongly agree to strongly disagree, etc. I’d also recommend a “tell us anything” section in the survey to let the students do a brain dump of anything they thought about the course so far. This is normally a big no-no in best research practices, but since this is an exploratory practice, the more information you can get about their experiences, the better. I know that for many IDs and teachers, who have been working around the clock due to COVID-19, the survey is also a great place to ask if the students encountered any bugs, errors, or anything platform related. It’s really easy to miss a typo or a similar mistake if you are producing course after course and running on only coffee and will power. Lastly, since you will be conducting interviews afterwards, make sure there is a question about conducting a follow up with the students! If you don’t have this section, it means you won’t know who to contact.

For creating the survey content, try to only ask important questions. I know this sounds like an obvious statement, but we have all taken a survey before that took what felt like an eternity to answer. Make these questions quick and succinct. You can ask questions about their behavioral patterns, content being relatable, learning behaviors, etc. One question that you should always ask as an ID or teacher is how long it took the students to complete the module. In my experience, this is the question that can produce answers you weren’t expecting. When my colleague and I were developing one of the courses in this leadership program, we were blown away by how long it was taking some learners while others were taking the expected amount of time. This became an excellent question to ask more about in the qualitative portion to hear their stories and uncover what they were experiencing.

Collecting the Data in the LMS

What’s the best way to start the data collection process? First, you need a type of survey tool. My favorite is Qualtrics because of its back-end customization and easy to read reports, but Google forms will also get the job done. Once your survey is complete, embed the link at the end of each module/week in your LMS. You can see an example of mine here in the edX platform:

Survey in LMS

You will want to include a survey for each module for “real time” feedback. Trying to ask students to provide feedback on all of the course’s content at the end of the term/semester will only give you an overview, but won’t provide specifics for each week. It’s simply too much information to store, retrieve, and critique. You want the feedback while it’s still fresh in their minds. I’d also recommend to make the survey required so that way you have enough responses to make an educated decision based on the feedback. If you have a classroom full of 25 students and only 2 provide feedback, it’s not as helpful compared to a higher number.

Analyzing the Survey Results

Once your survey responses are in, download the results via PDF formatting. It’s the easiest and cleanest way to read the data and to share it with appropriate stakeholders. Carefully observe the answers to each question and look for overarching patterns. Take note of the majority of answers for each question and see if there are any results that are surprising. You are looking for discrepancies among the data. Did one week receive heavy favoritism over another? Did students respond better to projects instead of other assignments? Was there more class participation at one interval of time compared to another? Look for these differences and find the ones that you can’t explain. For instance, I mentioned earlier how learners were devoting drastically different amounts of time in the module. This is a great example of something we couldn’t explain and we marked it down as a follow up question we wanted to learn more about. If you really want to be nerdy and precise with the quantitative data, you can find the mean, median, mode, and standard deviation. Depending upon your goal, it could be helpful, but this is certainly not needed in every instance.

At this point in time, reach out to the students who said they would be willing to participate in a follow up interview. You should be sending these invites while the survey is still fresh in their mind and you can reserve time on the calendar now to save that appointment. Coordinating schedules between several people easily takes the most amount of time from this entire process, so plan ahead!

Developing Interview Questions

From here, you can start to develop your interview questions. Your interview questions should all be open-ended and specific. For instance, here is a poor example of an interview question, “Did you enjoy the content from Week 1?” Here is an example of a thought-provoking question, “Week 1 was conceived as a basic overview of the course and was the lowest rated week on the feedback surveys. How could the content have been presented differently? What content or activities do you feel could have improved the experience?” Did you notice the differences between the questions? In the first question, all you will receive is a yes or no type of answer. In the second question, you are asking students to recall the week, their feelings, and how the learning experience can be enhanced.

Also, get as granular as you would like if it’s appropriate for your audience. I’ve found that when I conduct interviews and share the survey results with students in real-time, they find it enjoyable and want to participate more in the research. For instance, in my dissertation, I would cite percentages to back up my claims. One of my questions for students asked, “About 34% of Millennial Generation students answered that their advisor does not demonstrate concern for their social development. Why do you think they feel that way?” (Hobson, 2019). This type of question helped them remember the survey and how they answered. You could say the same with course questions like, “The majority of students said that Week 4 was their favorite week and that it was the most relevant to their job. Why was Week 4 more relevant compared to the other weeks and how would you like to see the other weeks become more relevant to your job?” Have about 8-10 questions ready to go for the interviews.

Hosting the Interview Sessions (Qual)

Now the fun begins! You will learn so much in a short amount of time. From my experience, the course improvement process can be more effective hosting small focus groups. I’ve found that students in small groups like 3-4 people can have a great conversation with each question bringing about several unique perspectives. Most of the time, when one student answers, another student wants to comment and make a point or counterpoint. Having more than this number though makes the interview process difficult to navigate. Not only do you need to be a facilitator for several people, you need to prepare for unexpected issues like Wi-Fi problems, microphone glitches, or some other technology issue, as I’m assuming you will be conducting your meeting through one of the video sharing platforms. It’s not impossible to manage a larger group, but I’d advise you to host several small groups.

Have a script prepared for everything you are going to be talking about. Here’s my structure:

Opening Statement (Thanking them for their time, purpose of the interview, etc.)

Introduction

Interview Questions

Closing Remarks

This structure creates a smooth transition from each part of the focus group. Consider recording this if it’s allowed and everyone attending the group is comfortable with it. This will allow you to go back and listen for smaller detailers you may have missed. I’d also strongly advise that you have another colleague take notes for you while you are conducting the interviews. This will allow you to pay closer attention to your students’ words and may lead to more questions. Trying to do the hosting and note taking duties at the same time usually leads to overlooking significant details.

Interpreting the Results

You now have all of the data you are looking for! Congrats! Review all of the answers from the focus groups and categorize the answers into their appropriate themes. Earlier, I mentioned themes such as behavioral patterns, content being relatable, and learning behaviors, just to give you an example. This will give you a clearer perspective of how all of the data links together from the course content to the survey to the interview findings. You can then draw conclusions based on all of these elements. Sometimes, you’ll find that many comments align from each group and it’s a crystal-clear answer of what students would like to see improved. Other times, it takes more effort and your experiences can guide you. I’ll give you an example of an easy solution and an example that took more time to think about.

For the easy one, after conducting three focus groups, we heard from learners that they wanted a way to take notes online as they progressed through their course. We were assuming that they could just use a Word doc or pen and paper to take notes, but students wanted a template to follow. My team and I came up with a “key takeaway” document that let students fill in notes on pre-populated information for each week. It was a no brainer and students loved it.

For one idea that took more time to develop, we heard that students were looking for more additional resources besides readings and videos. Given that most additional resources are either articles or videos, we had to get creative with this one. We decided to make a podcast based around the course’s content and embedded the podcast player into the course’s resource section. We chose this method as our targeted audience were busy adults whose demographics aligned with the typical podcast listener. We found out it was a success when students were raving about it in the discussion boards in the LMS.

Applying the Changes

At this point, you have your ideas outlined for improving the learning experience in your course. With all of your ideas, I would use some tactic when it comes to project management like a Trello board, Google Sheet, or be old school like me and use a white board. For each change, create an estimated time frame of how long it will take. For this process, be 100% honest with yourself and your schedule. If one change is going to take 3-6 months, then so be it. Overpromising on these changes can completely ruin the intention of revising the course in the first place.

And that ladies and gentlemen, is how to revise a course using student feedback. It’s a long yet incredibly rewarding process. By completing all of the above steps, you’ll have a blueprint for success and will make your course even better.

References:

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Hobson, L. A. (2019) Understanding online millennial generation students’ relationship perceptions with online academic advisors

Want to take your instructional design skills to the next level? Check out Instructional Design Institute.