What Did We Talk About Before Gen AI?

Every single year, without fail, educators are introduced to a new trend that’s promised to “revolutionize” education. We’ve been pitched this time and time again, with a promise of the latest, shiniest technology, learning strategy, tool, or technique that will truly make a difference. Most of them don’t pan out, even though they can be useful in particular circumstances. But that’s not exactly marketing friendly. “Can be quite helpful with enough training, dedication, resources, and budget!” doesn’t exactly scream, You need to pay attention to this idea.

And then… there’s Gen AI. Has it transformed or revolutionized education? Not yet. But the one undeniable thing it has done is disrupt education. It’s impossible to read an educational newsletter, email, journal, or anything else that isn’t plastered with AI topics. Planning to attend a learning and development conference soon? I hope you like AI.

Even scrolling through LinkedIn, every single post I read has some AI affiliation. It might be a generated image, a conversation about tools, a new approach to assessments, a policy update, or research on generative AI's impact on learning. This constant stream of AI content has fueled the rise of AI influencers. At the same time, it has prompted others to dream of escaping to Green Bank, West Virginia, the town that banned wi-fi, cell phones, and microwaves.

While I am always in favor of being informed about the latest technology, this did have me thinking about the “before times.” What were we talking about before Gen AI? Pre-2021, what were we sharing about instructional design, teaching, and learning? Let’s go all the way back to a few years ago and remember the good ol’ days!

Zoom Fatigue and Camera Requirement

“You’re on mute.” Ah yes, the pandemic times! Back when I lost all sense of time and understanding:

Do you remember when your life became Zoom? In 2019, I had a hybrid schedule: two days at home, three days in the office, or flipped depending on my projects. At first, I found the transition to working full-time from home easy. But after a few weeks of the same routine, it became mentally draining. The odd part about working remotely was that work-life balance didn’t really exist. I would start working at 5 AM, and half my team was already online. I could send an email at 9 PM and get a reply almost immediately.

Of course, part of what contributed to this was the way we were all trying to escape reality—by connecting with friends and family on Zoom. Spend nine hours on Zoom for work, then hop on more calls for a birthday party or a fantasy football league. Nothing quite prepared us for being on camera twelve hours a day. One of the strangest parts, which I still haven’t figured out yet, is the etiquette around eating on camera.

So how does this relate to teaching and instructional design? For one, it raised questions about synchronous sessions, specifically, whether students should be required to keep their cameras on. Should it be mandatory or not? For many empathic educators, it quickly became clear that requiring cameras wasn’t feasible for a number of reasons. There’s been growing advocacy for further research around this issue, and this quote from Inside Higher Ed captures it well:

“Yet a cursory search of the literature shows research relating to communication, technology and the use of cameras as data-gathering tools but none on the necessity of cameras for learning or engagement. And, in fact, the added anxiety for some students who are asked to turn their cameras on may actually diminish their participation, as they feel a need to monitor their home, their family members and their intimate spaces while attempting to attend to classroom interactions” (Finders & Muñoz, 2021).

While some folks have said, “Glad that’s over—let’s go back to in-person courses,” the pandemic left a lasting impression on both remote work and online learning (more on this later). One element I genuinely enjoyed while teaching during the pandemic was the flexibility to host live sessions within my asynchronous courses. I still do this for my students in the Ed.D. Program in Applied Learning Sciences at the University of Miami. I found that even one session a week became a focal point of the course, especially from the students' feedback. And it seems like I wasn’t alone in this.

I recently came across an article from Harvard Business Publishing that focused on the importance of human connection in asynchronous courses. The author, Trish Berg, associate professor of management at Heidelberg University in Tiffin, Ohio, mentioned,

“I believe universities should follow suit and prioritize adding synchronous moments into asynchronous learning. After all, as college educators, we are preparing our students for their future careers, and many of them will work remotely. Teaching them how to stay connected in a remote world is a key part of their learning process and career preparation” (2025).

That little bit of human connectivity goes a long way.

Learning Experience Design VS Instructional Design

Ah yes, the great debate. What are we? What should we be called? Are we learning experience designers or instructional designers? Is there actually a difference? Does it matter?

I assume most folks think of this as a newer topic, but there was already a strong push to rebrand instructional design back in 2015. Connie Malamed, founder of The eLearning Coach, wrote a thought-provoking piece called “Instructional Design Needs A New Name!” In the article, Malamed explains how instructional design has evolved, with a growing emphasis on user needs, learning sciences, and the overall experience. She argued that focusing solely on “instruction” is outdated and that it’s time to reinvent the field.

Niels Floor, author of This Is Learning Experience Design and the person who claims to have coined the term “LXD” back in 2007, offered a different take. He expanded on his perspective in an article titled “Learning Experience Design is not a New Name for Instructional Design.” These pieces sparked plenty of conversation, spilling over into LinkedIn and Reddit. It wasn’t long before practitioners in higher education picked up on the trend. Soon, universities like LSU and NU began offering certificates in Learning Experience Design.

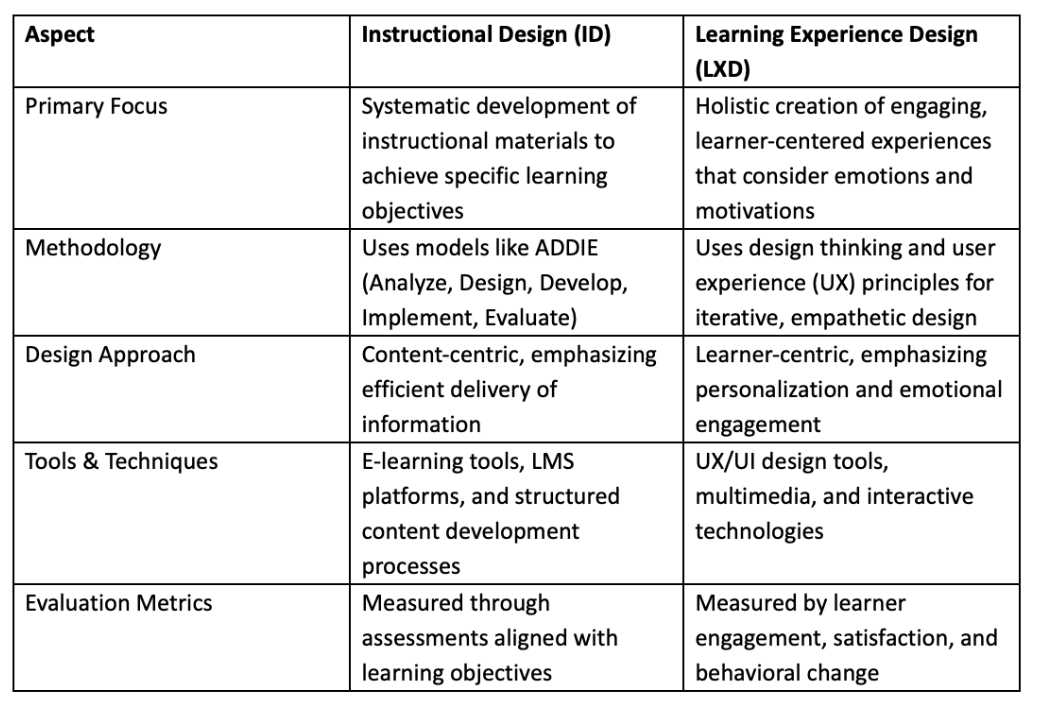

So, what’s the verdict? Are they different? From interviewing actual Learning Experience Designers, here are a few key points they shared about the differences:

Now, I promise you, some instructional designers have read these discussions and thought, But I already do all of these things, so what does that mean? And that’s exactly the issue. There are overlaps and gray areas. Some instructional designers do everything a learning experience designer does, while others are stuck in order-taker roles. An LXD would never dream of skipping research and jumping straight into building a quick training with an authoring tool. That kind of task could fall under an instructional designer’s role, but there are plenty of IDs who would never rush their design process and who would push back firmly on that kind of request.

While researching this topic, I found that people are still actively talking about it, and I’m sure the conversation will continue until the next big thing comes along. In my opinion, it all comes down to your employer and what they expect from you when it comes to designing learning experiences. They can call you whatever they want. Sometimes, those titles are at least consistent, which helps create a bit of stability and standardization.

For example, government roles in the United States are often titled Instructional Systems Specialist, and you can find many of these positions on USAJobs.gov. Some organizations have gone with a hybrid title, like Learning Designer. I don’t think we’ll ever land on a clean, conclusive stance, because our field doesn’t have an industry-recognized certification or license. We don’t have anything equivalent to a CPA, PMP, or CSM. There are organizations that are certainly respected, such as Quality Matters (QM) and the Association for Talent Development (ATD), but they haven’t created enough momentum to standardize a title or define a common set of responsibilities for an entire industry. All of this becomes even murkier when we think about the differences of sectors within higher education, corporate, non-profit, K-12, etc. At the end of the day, as long as I can design meaningful, relevant, and interesting learning experiences, you can call me whatever you want .

If you want to dive into this conversation more, I’d recommend watching Dr. Ray Pastore’s video that breaks down LXD vs ID. If you're thinking about the future of titles, you can read one of my newer articles. I hope you have your tinfoil hat on standby for that one.

Misconceptions of Online Learning

The pandemic brought a spotlight to the world of online learning, and maybe not for the better. With the immediate shutdown of face-to-face classes, every course had to become an “online” course. In reality, this was an emergency situation, and the courses created were built out of necessity for survival. There was no plan in place. It was common to hear that universities were trying to “flip” their courses online. The rush to put everything together in this way often led to learning experiences that felt bleak and disappointing.

Faculty weren’t to blame for this though. There wasn’t time. There weren’t enough resources, enough budget, or enough support. For many, this was their first time teaching in this modality, and they weren’t properly trained or equipped to manage online learning.

What broke the hearts of instructional designers and educational technologists across higher education was hearing how all online learning was being lumped together. There are incredible online courses and programs that exist, built on decades of research and best practices. Overnight, it felt like all of that was dismissed. This isn’t a new issue. We’ve been pushing back for years against the misconception that online learning is inherently inferior to in-person learning.

One article that addressed these challenges was called The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. The authors—Charles Hodges, Stephanie Moore, Barb Lockee, Torrey Trust, and Aaron Bond—did an excellent job of shifting the conversation around online learning and introduced a key new term: emergency remote teaching.

According to the authors,

“Researchers in educational technology, specifically in the subdiscipline of online and distance learning, have carefully defined terms over the years to distinguish between the highly variable design solutions that have been developed and implemented: distance learning, distributed learning, blended learning, online learning, mobile learning, and others. Yet an understanding of the important differences has mostly not diffused beyond the insular world of educational technology and instructional design researchers and professionals. Here, we want to offer an important discussion around the terminology and formally propose a specific term for the type of instruction being delivered in these pressing circumstances: emergency remote teaching” (2020).

This article spread quickly and inspired other educators to contribute their own content. One of my most popular blog posts, How to Convert a Face-to-Face Class to Online/Remote Learning, came from that same time period. While it was truly a chaotic moment, it brought a new sense of community to those of us working in edtech and online learning.

There were certainly some benefits of this exposure to the general population. For one, instructional designers became the emergency contact for universities. Victoria Abramenka-Lachheb, Ahmed Lachheb, Amaury Cesar de Siqueira, and Lesa Huber dubbed us as “first responders,” and I think that’s quite fitting. I spoke with thousands of representatives at higher education institutions during this timeframe, mainly because they had never heard of instructional design before and were shocked that this was even a field. Yes indeed, magical unicorns exist who can transform your learning experiences, and you should hire them. It's a beautiful thing to hear about universities hiring their first instructional designers, who are still there today and thriving.

The second benefit is finally getting through to the average person about the importance of catering to learning preferences and students’ diverse needs. For some students, online learning is simply better. It’s flexible, more affordable, and more accessible. It works. But it wasn’t just students. Some faculty members emerged as strong advocates for online learning. The script flipped, and you began to hear preferences for blended and online offerings. Despite the many ups and downs that came with the pandemic and online learning experiences, permanent and positive changes have taken hold.

Learning Analytics

What does educational data mining (EDM), business intelligence in education, and learning management system logs have in common? Well, they are the roots of learning analytics. Phil Long and George Siemens were the pioneers of learning analytics back in 2011. This was marked by the first International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK11). They described the need for this field because of :

The growth of data surpasses the ability of organizations to make sense of it. This concern is particularly pronounced in relation to knowledge, teaching, and learning.

Learning institutions and corporations make little use of the data learners “throw off” in the process of accessing learning materials, interacting with educators and peers, and creating new content.

In an age where educational institutions are under growing pressure to reduce costs and increase efficiency, analytics promises to be an important lens through which to view and plan for change at course and institutions levels.

They were absolutely spot on and this field evolved with each passing year. Concepts such as predictive analytics and learning analytics literacy began to emerge. Wow, doesn’t that sound familiar with AI literacy! Anyway, from here, and where we left off with before the Gen AI boom was talking about two key areas.

The first area is data security and privacy. In 2017, an article from EDUCAUSE titled 7 Things You Should Know About How Learning Data Impacts Privacy highlighted the dangers and pitfalls of data. The article stated, “Given the multiplicity of sources and uses of learning data, and in light of the evolving interests of service providers, managing the privacy of learning data requires user education and awareness, as well as policies and enforcement aligned with the emerging impacts of learning data on privacy” (EDUCAUSE, 2017). While some educators emphasized these concerns around security and the unknown, institutions were still struggling to figure out how to use learning analytics in a meaningful way. Over time, more use cases and research began to emerge.

The second area is with an exploration of the positives of learning analytics. Adedayo Taofeek Quadri and Nurbiha Shukor published an article in 2021 in the International Journal of Emerging Technologies called The Benefits of Learning Analytics to Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. In this review, the researchers found that benefits of learning analytics were numerous such as:

Improves student performance by identifying learning outcomes and areas needing support during the learning process.

Reveals learning behaviors and endurance, helping educators understand how students interact with digital tools like e-learning and mobile learning.

Supports adaptive learning by helping instructors tailor content based on learner needs.

Enables early interventions through tools like Course Signals, which combine LMS data, demographics, and prior performance to deliver real-time, personalized feedback.

Predicts student outcomes such as grades, graduation rates, and dropouts using statistical models.

Informs curriculum development by identifying course dependencies and content gaps, helping institutions redesign courses and programs for better learning experiences.

Recommends personalized learning resources and detects unproductive behaviors and affective states to enhance student self-awareness and reflection.

Boosts instructor performance by using analytics to evaluate and improve teaching strategies, pedagogy, and instructional decision-making.

Strengthens faculty data literacy, encouraging evidence-based reflection and peer collaboration to enhance teaching quality.

Stories of using learning analytics for student success became a focal point such as with Open University and Georgia State. It’s so fascinating to see one topic emerge over the years to the point of where you can go to school for a master’s degree in learning analytics. If you don’t know where to begin, EDUCAUSE and EdTech Books have a wealth of information for you.

As much as I would love to keep on reminiscing with you, I do need to wrap this up somewhere. So, here are a few quick honorable mentions:

The Metaverse (RIP)

Extended Reality (XR)

Microlearning

Gamification

Social Learning

Mobile Learning

My main takeaway from writing this article was a bit unsettling. I had to genuinely reflect on what we were discussing only three years ago. Since then, I’ve thrown myself into the deep end of AI, learning as much as possible, experimenting, and sharing the results with folks like you. In doing so, I set aside other topics I was passionate about, and revisiting them has rekindled some old feelings. It's a good reminder: don’t lose sight of what truly matters.

What topic were you obsessed with before the Gen AI boom? Let me know in the comments below!

References:

Abramenka-Lachheb, V., Lachheb, A., de Siqueira, A. C., & Huber, L. (2021). Instructional Designers as “First Responders” Helping Faculty Teach in the Coronavirus Crisis. Journal of Teaching and Learning With Technology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/jotlt.v10i1.31368

Berg, T. (2025, May 15). 3 ways to foster human connection in asynchronous courses. Harvard Business Publishing Education. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/asynchronous-online-courses-human-connection-strategies

Dimeo, J. (2017, July 18). Georgia State improves student outcomes with data. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2017/07/19/georgia-state-improves-student-outcomes-data

EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. (2017). 7 things you should know about privacy and learning data. EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2017/5/eli7144.pdf

Evans, L. (n.d.). Instructional design vs. learning experience design: What’s the difference? USD Online Degrees. https://onlinedegrees.sandiego.edu/instructional-design-vs-learning-experience-design/

Finders, M., & Muñoz, J. (2021, March 3). Why it’s wrong to require students to keep their cameras on in online classes[Opinion]. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/03/03/why-its-wrong-require-students-keep-their-cameras-online-classes-opinion

Lederman, D. (2023, August 25). Report: Majority of faculty prefers in-person teaching. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2023/08/25/report-majority-faculty-prefers-person-teaching

Long, P., & Siemens, G. (Eds.). (2011). Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK '11). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2090116

Quadri, A. T., & Shukor, N. A. (2021). The Benefits of Learning Analytics to Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 16(23), pp. 4–15. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v16i23.27471

Siemens, G., & Long, P. (2011). Penetrating the Fog: Analytics in Learning and Education. EDUCAUSE Review, 46(5), 30–40.

Vahdat, L., Griffin, A., Jain, M., Levy, A., Mastrogiannis, D., & Das, A. K. (2017). Data sharing practices and data availability: A survey of 1,000 highly cited papers. Scientific Data, 4, Article 170171. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.171

A huge thank you to our sponsors! Consider supporting those who support our show!